Jeffrey Zeldman is a name that has become synonymous with the rise of the internet. His contributions to the field of web design and our understanding of how to build on the web have been critical. He wrote the field defining book, Designing With Web Standards, which paved the way to understanding the importance of separating content from style on the web at a point when no one knew what the web could be.

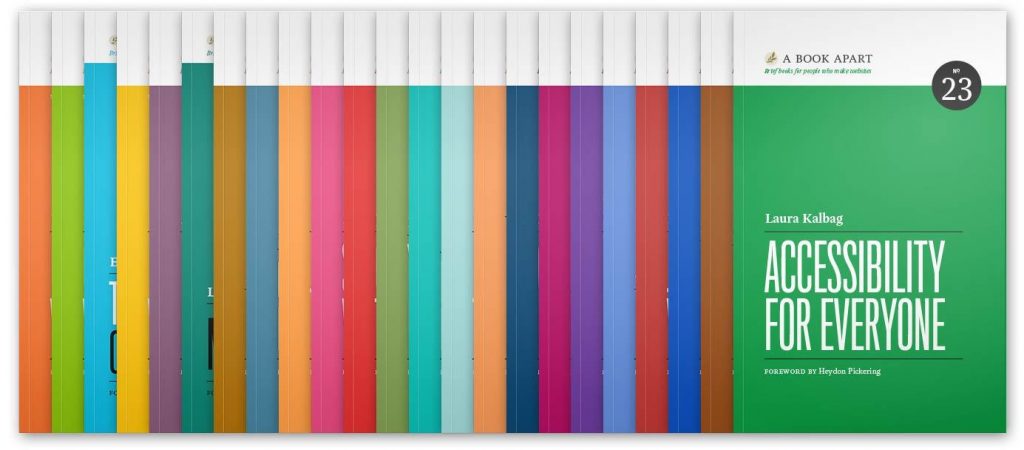

In addition to his book, Jeffrey started his seminal publication, A List Apart, which is perhaps the longest running online publication about web design and development out there today. The magazine has since published many of the most important writings and concepts in the field and introduced many of the most prolific web design thinkers over the past few decades. Zeldman is also a serial entrepreneur, having started a successful conference series (An Event Apart) and a book imprint (A Book Apart) based on the A List Apart brand. He also founded the incredibly successful design studio, Happy Cog in New York City and Philadelphia.

My introduction to his work spans back to the early days of the internet, and like many others I sat dumbfounded as I read through his book on web standards. It changed everything I knew about web design in the span of a couple hundred pages. His ideas would eventually lead me to work with him at A List Apart for over a decade. During that time I gleaned a lot of insights (from Jeffrey himself as an informal mentor) into what it takes to run a series of successful businesses and a design studio while continuing to influence a community around you by talking about what matters.

After a decade-plus of building Happy Cog into one of the foremost web design agencies in the US, he decided to step away and start a new studio endeavor—a move that surprised many and one that runs counter to what we think of as a normal career trajectory (designer leaves a successful studio to start a new studio) . This newest project though, lovingly titled studio.zeldman, was born of the idea of getting back to basics and doing what it is he loves doing best—design.

Jeffrey has a unique ability to suddenly change directions, switch things up and re-invent himself and the work he does to suit an ever changing, ever more challenging field of web design. I caught up with him to talk a bit about entrepreneurship, his new studio venture, and the importance of embracing change.

You spent a decade and a half building your first studio, Happy Cog. What was the driving force behind making a change, pivoting so to speak, and starting your new studio (studio.zeldman)?

Happy Cog is a great studio. I’m proud of the work we did, proud of the many incredibly talented designers, developers, strategists, and project managers who came of age professionally there. A list of our past employees is like a who’s who of digital design. Hell, it’s a who’s who of design—no digital qualifier needed.

But there’s a huge difference between starting a design firm and running one. It’s the difference between doing the work yourself and managing others. Being a figurehead at a design studio with an international reputation is great for your ego, but it’s hell on your hand skills. Especially on the web, you need to keep your hands in—not rely on other people to keep their hands in for you. In this area of design, you don’t just talk about the thing you’re making, don’t just plan it—you actually touch it every day. I missed that.

Plus, once your studio is established, you get known for doing a certain kind of work for a certain class of client. For Happy Cog, that’s a beautiful thing. But I was ready for a new set of challenges.

Stepping away from a business that you built from the ground up to start over can be tough (and daunting). What are some of the things you are doing differently this time around?

Well, during the last 12 or so years I was at Happy Cog, I had also started other, related businesses—like An Event Apart with Eric Meyer, and A Book Apart with Jason Santa Maria. And I learned not only the joy of starting new things but also the terror of having other people depend on you. Of worrying that your product might one day no longer be valued. That you could go broke, lose your home, and so on. Things have gone well—don’t get me wrong. But dealing with those kinds of worries and exaltations has deepened my compassion toward people who start and run businesses—my clients. If there was still some small immature part of me as a designer that saw the client merely as a means toward an end—the end being the display of my creative talent and the fattening of my bank account—after running my own businesses besides the studio, I have a deeper kinship with the people I serve. In the past, I never forgot the person who had to use the site or application I was designing. Now I also never forget the people who work on the business. And as I am more and more empathetic to my clients, they become more and more empathetic to their customers—which makes for better design.

Jeffrey Zeldman started his new studio, studio.zeldman, after leaving his long time design studio, Happy Cog.

In other ways, I run studio.zeldman the way I ran Happy Cog when I was starting out—namely, I run it as a collaboration studio, where I can bring in just the right freelance consultants for each project. There are pluses and minuses both ways. With a steady staff of employees who work with you day in and day out, you develop a second family of sorts—where you mentor, but you also learn. The same way I learn more from my daughter than I teach her, I learned more interacting with a permanent staff than I ever taught any of them. On the minus side, you have all these people relying on you, and payroll becomes a beast you have to feed. You have less discretion over which projects and clients you can say no to.

But the way I ran Happy Cog in 1999, and the way I’ve organized studio.zeldman now, it’s only about the work. I can say no to anything. I can also say yes to things I maybe couldn’t say yes to if I always worked with the same staff.

I’m also focusing as much as possible on the part of the experience my colleagues and I are best at: the front part. We’re not trying to be a one-stop shop. If you need to migrate from Drupal to WordPress, or whatever, we can connect you to great shops that specialize in that sort of thing. What we specialize in is research and strategy in service of the brand and the customer. We design experiences that meet real needs and are accessible to everyone, on any device. They may be jazzier on a modern browser in an up-to-date operating system, but they will be readable and functional and beautiful for any human, on any device. Designing beautiful reading and interactive experiences is always what I loved and what we were best at, but we used to try to deliver everything from the first phone call to the last reboot of the server. Now we deliver strategy and the front-end components, typically in the form of a documented pattern library that’s unique to the client and their brand.

Change is a byproduct of this industry (web design), and it’s been relentless since we started down the road of building a world wide internet-based platform. As you’ve been laying the groundwork for studio.zeldman, what have been some of the major differences between starting a studio 16 years ago vs. today?

In the old days, I had to fight to persuade a client to consider allowing me to make their website accessible to people with disabilities. I had to persuade them to let me make a site that would work for anyone, on any device—not just in Internet Explorer on Windows, or whatever. I had to sell them on clean typography and whitespace—on doing less, better, instead of trying to do everything, badly. Now I no longer have to sell anyone on those ideas—at least no one who comes to my studio. Clients are smart. They know it’s about the customer, not them. They know it has to be responsive, in every sense of that word. They know speed and performance matter; that websites don’t have to look the same in every browser; that people expect a brand to function the same way between apps and the web, between phone and desktop, but they don’t expect the apps or the website to act or look the same. They get that function is a huge brand attribute, performance is a huge brand attribute, that function and performance matter more to their customers than the minutia we all cared about twenty years ago. All those battles we engaged in are done. Hope and reason prevailed. Now we can spend our time collaborating on great experiences instead of arguing about rounded corners.

At the risk of repeating myself, what’s also different is that, these days, instead of negotiating a set list of deliverables, clients and designers agree to focus on process. We don’t argue about revisions, we expect to make them. They aren’t client changes, they’re iterations. The user is in charge, not us, not our clients.

I always had good relationships with good clients, but today it feels like that’s on a higher level than was possible in the past. We view our work as 100% collaborative. We work fast, we work low-fi. We don’t get hung up on details until it is time to fill details in. We sketch, we share, we talk. All very different from the formal presentations of the past. We don’t hold our work behind a curtain and present it in a series of ritual dances; we share constantly, requesting feedback all the time, showing our clients how to share the kind of feedback that helps us design a better product (not ego-driven feedback).

Instead of shipping templates installed in a CMS, more and more we ship pattern libraries. And we involve the client in every design decision, so that when it’s time for them to take the pattern library and run with it, they can do as good a job with it as we would have—they know it as intimately as we do, because it’s as much their work as ours (even if they didn’t create the elements in Illustrator or Sketch or a code editor).

It also seems like it’s easier these days to be completely honest with clients. We never hesitate to tell a client when we don’t know the answer to a question. Modern Westerners are exposed to more new information in a day than our great-grandparents were exposed to during their entire lifetimes. The human mind can only take in so much. Nobody knows all the answers. Nobody expects their designer to know all the answers.

One of the things I’ve admired most about you over the years is your willingness to explore new opportunities—taking risks when they seemed advantageous. What role should risk play in the life of a designer?

It depends on their family situation, their good fortune, their emotional comfort with anxiety, and other factors. I read today that entrepreneurs almost always broke rules during their adolescence. I shoplifted and smoked pot during mine. Not that I recommend anyone do those things. It does make sense, though, that a smart person who doesn’t fit into their society quite as comfortably as their peers would act out during the transition to early adulthood, and could end up inventing a position for themselves because no position they were offered by others ever fit, exactly.

Now, I have a mild anxiety disorder. I feel more stress than most people. I stress about things that don’t even slightly bother most people. Until I got sober I medicated that anxiety with alcohol. Once I got sober, which was around 25 years ago, I had to do something with all that anxiety, all that energy. So I channeled it into work. I wasn’t planning to go freelance and to eventually start my own companies. Hell, as a kid, I didn’t even think I would be employable when I grew up. You wouldn’t think someone as anxious as I am would thrive taking risks that could cost him his home. And, in case my remarks are misleading, I should add that I’m no thrill junkie. I don’t get off on the idea that I might lose my home. I’m not like one of those people who can only have sex in a public place, because the thrill of possibly getting caught excites them. No. I actually hate the risk. If I could do what I do and get a steady paycheck every month, I’d love that. Especially if it was a large paycheck. But I bridle under other people’s authority. I do my worst work for micromanagers. To some extent, in any job, I feel controlled. I am only able to be myself, and to do the work I was put here to do, when I am free—and I am only free when working for myself. The ability to say yes or no to a gig: that means everything.

Entrepreneurship and starting a studio means sacrificing a reliable/semi-stable job and paycheck, yet you chose to peel off and go your own way. What was it that made you decide that working for yourself was the only real option?

I sucked as an employee, and everyone I ever worked for let me know. It was never about the quality of my work—that was always, apparently, good. It was about my attitude, my resentment at being trapped inside a situation of utmost conformity, the perpetual scowl on my face (even when I felt neutral or even happy). I almost always felt smarter than the people for whom I worked or the situations in which I worked. Let me be clear: I have worked for some incredible people, who were smarter and more talented than I will ever be. But in those cases, I was miserable because of the situation—because of some constraint these people imposed (or I felt that they imposed) which kept me from doing good work.

A List Apart, Jeffrey Zeldman’s seminal publication, has published many of the most important writing in the web design field.

When the web came along, it was almost too easy to work for yourself, do everything yourself, and make a living. I had already been freelancing for ten years as a writer and art director, so it was not scary to freelance as a designer. I just fell into it.

And now I could never leave.

It’s like New York, where I have lived since 1988. I love it here. But I can’t really afford it. Nobody can. And yet I cannot leave.

Well, that’s how it is running your own design studio. There are huge highs when you win. There are crushing lows when you lose, or when you fail to deliver the best possible solution to the client’s problem. There are days when money is not a concern, and others when you are dead broke. An adult my age, with my skills, should not have to face an empty bank account. Yet sometimes I do. But what choice do I have? I’ve had too many years working for myself. I know this boss’s flaws (most of them, anyway). I’m too old to start learning how to work for anybody else.

I know that through your work with A List Apart, and now studio.zeldman, you are a big believer in working with a geographically distributed team to collaborate on projects. What do you feel are are the benefits of working with individuals from around the world?

Design is a global community. Web-focused design especially so. I love my people in Switzerland and Seattle, in Chicago and Greece. I love thinking whose time zone I’ll be in when I travel for business. Mostly I like picking the right person for a particular task and working with them, regardless of where in the world they live. I wish there were less nationalism in the world today, and more brotherhood.

You step through a door and are confronted with a much younger version of yourself. He is currently in the process of weighing his options and contemplating going out on his own. What is some of the advice that you would impart to this ambitious young designer?

For at least the first five years, don’t worry about how you’re doing, focus on the work. Don’t bog down in who’s doing better than you, how much you’re earning versus the person in the next cubicle, why you didn’t land a particular job. Stay positive, stay focused on the people you’re designing for. Think what they need. Design that. Then design something better.

Don’t get so attached to your work that you can’t take criticism or suggestions. Work low-fi and fast when beginning a project, so that it’s all about the ideas, and not about the 14 hours you spent creating gradients in Photoshop. Sketch first and sketch fast. Details are for later.

Especially in interaction design, test your work on people, and do it in a way that provides actual data. (Asking leading questions isn’t getting data, it’s just wrapping your bias in pseudoscience.) Test, but don’t be a slave to data. Trust your gut, too. Remember that data is only as good as the questions you ask, and the questions are only as good as the person asking them. Data doesn’t give you the answers, it just gives you something to interpret; that interpretation will give you *part* of the answer.

Hold off on execution as long as you can. This is tough, especially when you’re new to design. You want to jump in and make something beautiful. But wait. Ideas, first. Ideas are often ugly. And that’s okay.

Don’t be such a slave to your own style that you design inappropriately for the user or the brand. I love 90s club poster style but I wouldn’t use it for a bank’s website, and neither should you.

Be humble and listen, but stand up for your ideas when they are right.

Don’t make the client a villain. Make them a partner.

Don’t be afraid to do more work. Don’t think that all the work you do has to show up on the page or the screen. Sometimes the more work you do, the less you ultimately create. Better to play the three notes the song needs than a hundred meaningless guitar licks.

Stand up for your user. Stand up for your partner. Never betray your partner or make deals behind your partner’s back. Be inclusive. As you make progress, reach out a hand to those coming along behind you, especially if they are struggling. Seek diversity in your team.

Design is a job, and it is frustrating and difficult, but it is also a form of love. You are making the world better when you solve someone else’s problem. Be proud—but not arrogant. Never ask the client where they went to design school. Never assume you are better than the client just because they can’t tell Helvetica from Arial.

You’ve authored or been involved with publishing several of the most iconic books about the Web—helping to launch and flesh out your career, what role should media types such as blogs, social media and video play in the development of a designer’s career?

For me, possibly because I’ve just been at it so long, that writing definitely helped define my career. It also didn’t hurt that I came along as we were starting to solve some of the big, initial problems in designing a new medium—like, should there be technical standards, and if so, which ones, and how do we persuade others to adapt them so they can truly work the way standards are supposed to work. So the writing I was doing to figure out how things worked ended up changing how other people approached the work, and that was gratifying (because it helped make the medium possible), and it probably helped my career, too. But that’s a side effect. The most important thing it did was help me develop convictions as a designer—help me establish design principles that mattered to me and that have guided my work (and thus afforded me a career). You don’t have to be famous to have a strong design career. But you do have to have convictions and principles. And writing is a great way to develop those. Whether your blog gets ten thousand readers or five, if it helps you evolve in your design thinking, it’s good for you.

A Book Apart, a series of short books for those building the web.

Plus all that writing makes the words come more easily when you’re in a meeting with colleagues or clients and being challenged to explain or defend a design decision. If you write often enough, you know why you do the things you do, and you can articulate persuasively right there in the room. Which helps you sell your best work. You can’t do it if you’re tongue-tied. And writing is the start to untying the tongue.

Lastly, the age old question (and because you have spent a significant amount of time as a publisher of fine books), do you think print is dead?

You can hardly walk around in my apartment because of all the books. Shelves? We’ve used up every inch of them, and are on to the furniture. There are books stacked on the table, books on the settee and couch, books on the cabinets and printers and scanners. I read and collect digital books, too, of course—I even publish some—but some ideas need to live in paper.

Until recently, paper was the only format that even offered the remote possibility of immortality. All the old storage formats are dead. Microfiche? Along with the old digital storage formats. When you’re finished buying the Brooklyn Bridge, maybe I could sell you a Zip disk or Syquest. Nothing is eternal. Only paper came close, until we had HTML. HTML (with its helpers, CSS and JavaScript and image files and SVG) is another way besides print that our ideas may survive a thousand years. (Whether we ourselves will is another story.)

But print is certainly not going to be killed by some temporary format, on a device like the iPad or Kindle that is fun and useful for now, but not going to be around forever.

How publishers survive to keep making books is a question. I don’t have the answer. And I’m a publisher myself. For a while I thought small presses like A Book Apart that build one-on-one relationships with readers were maybe part of the answer. I don’t know about that any more. I try to find good writers with good design stories to tell, I talk to the people who read our stuff, I try to respond to our audience and their needs. What else can you do?

– – –

Erin Lynch is a designer, writer, and educator living in Vancouver, WA. He owns the design studio, Shop, and is an editor at The Portland Egotist. Reach out and make friends on Twitter: @erinlynch.

Erin Lynch is a designer, writer, and educator living in Vancouver, WA. He owns the design studio, Shop, and is an editor at The Portland Egotist. Reach out and make friends on Twitter: @erinlynch.