It always amazes me during the interview process when I get deep into exploring the unique path a designer has taken to owning their own studio. The experiences of each creative entrepreneur are diverse, their roads laden with failures and successes. Yet, the driving need for independence and forging one’s own way seem to be central themes that appear repeatedly.

The role of a studio owner is one that comes with many different hats to be sure. It can be a liberating, empowering experience as you build your roster of clients from the ground up, and eventually add to your team others who share your studio’s vision. It can also be an environment of risk and fear. You, as the head of your studio, are responsible for the collective welfare of the team. The proverbial buck, so to speak, stopping solely with you. Yet that risk and fear, which might dissuade many from making the transition from gun-for-hire or staffer to full fledged studio owner, can be harnessed and used as a powerful tool to propel your studio to new heights. That, I believe, is one of the deeper secrets of entrepreneurship. You can embrace risk and fear, and make them into something positive.

Brian Kappel’s road to studio ownership, as the head of Space Monkey Designs, took over a decade to travel. He spent that time honing his craft, building valuable 2D and 3D design skills, and forming his ideas of what running a studio meant to him. His work with NIKE paved the way to the larger world of design, but an insatiable desire to do more (another common trait amongst studio owners) propelled him to where he is today. In our discussion, we covered topics related to risk, fear, and why being a generalist can be creatively rewarding.

Many times it seems as if the destinations we reach as designers are each the direct culmination of a diverse and varied career. For those not familiar with your work, can you briefly take us through your career path?

Diverse and varied are two words that best describe my background. To really paint the full picture, I do have to back it up to my younger years. I was raised to work; if you want something, you work for it. If you don’t like something, you either shut your mouth and get through it or change it. I grew up working three jobs (or more) in the summer, and it really set the tone for my professional career.

I graduated from Penn State in 1998. During my time in school, I worked part time for NIKE, as well as being a student illustrator for the School of Science. I had a Sports Marketing Internship at NIKE in the summer of 1997. There I really got my first taste of corporate level guerilla marketing initiatives and all the work that went into them. After school, I wanted to continue on with NIKE, but found that I only really had strong opportunities in Sports Marketing. I wanted to be in design, but being that my focus in school was drawing and painting, I didn’t have a portfolio (or a design degree) that would put me in line for an entry level NIKE Design job. So, after a year of pulling chain link fence for a local athletic facility, I landed a Production Art (PA) job.

That production job was essentially a crash course and my introduction to computer design and the process of ideation as I had to mirror the higher level designers, creating their schematics and production files. While doing this, I learned the process and started to design tees on my own. I spent time being critiqued and honing my skills to the point that I was the only PA who had tees going to market. After 18 months I got my first apparel graphic design job. I worked for both Brand Jordan and Nike Team Sports before leaving the company after 5 ½ years.

I realized that there was much more in the design world that I was not coming into contact with. During my time at NIKE, I would also work freelance, after-hours from my house. I worked with other agencies, small businesses, basically anyone I could find who was willing to toss some cash my way for design. I also continued to draw and paint, trying to incorporate them as much as I could.

When I left NIKE, I moved into the agency world in Portland, where I spent about 10 years working on everything from retail architecture and signage, to customization and events. I learned more in these years than any other period. In apparel graphics, I learned the craft of 2D design. Through the experiences that followed I learned a holistic approach to design that moves from 2D to 3D, and how the two play together to create dynamic stories.

The experience of jumping into new challenges, constantly pushing to be better, always taking on more work, continuing to do freelance no matter where I was, and ALWAYS making time to draw and paint led me to where I am now. Having a solid blue collar work ethic paved the way for one unbelievable experience after another. (I am currently working on a book called “Plight of the Blue Collar Designer”, aimed at recognizing and elevating the hard work that goes into design, while trying to bust the “designer” stereotype).

Some might consider an apparel designer position at a company like Nike as a brass ring in their career path. What made you decide that starting your own studio was the next, best step in the evolution of your career?

Whoops, I jumped ahead in my rant above.

YES, most sane people would look at that and say, “Damn, I made it!” And they would be right. What pushed me past the notion of being a “lifer” was a simple poster created for an internal sales meeting. Seeing that work made me realize there was a bigger design world that I was not interacting with. I started asking questions. I learned Photoshop and incorporated it into my designs. When I was comfortable with that I started breaking into 3D design. I learned Sketchup. I began learning to think in three dimensions and incorporating that knowledge with my new 2D approach. There was a lot to learn.

Establishing my own studio didn’t come until 10 years after leaving NIKE—once I felt that my skills were diverse enough that I could engage with a variety of clients across different project types. I’m fortunate enough to have developed skills that allow me to do everything from traditional sketching to complex renderings, identities and branding, graphic tees, built-by-hand wood projects all the way to customization.

Many designers have a desire to strike out on their own, but few actually take up the challenge. What skills/traits, in your mind, are essential to starting a studio?

Great question. My biggest point of preaching for young designers is KNOW WHO YOU ARE. If you cannot authentically represent yourself, then you are doomed to either becoming forgettable, or getting into a situation where you overpromise and underdeliver. You have to know who you are, and what you ROCK at.

When people turn to creatives, they are wanting an authority. And designers are that authority. “People” in general are intimidated by design or think that design is something that “anyone can do.” It is our job to arrive at solutions that sit outside the scope of everyday thought.

For anyone going out on their own, I would say confidence, not ego, is essential. At the same time, understanding that you cannot do it all, and that you need to align with vendors/partners that share your approach, whatever that may be. Your POV is your biggest sellable asset, as long as it is a direct representation of the work that you are capable of producing.

There is a big difference in working as part of a large agency or corporate design team and working for yourself and starting a small studio. What has been your biggest challenge in transitioning from being part of a team to owning and running your own studio?

I really enjoy collaboration and the work that comes from bouncing ideas off of one another in an agency setting. Honestly…it was my favorite part of the agency setting. People from different backgrounds with different skill sets, throwing ideas into the pot and seeing what solutions cook down. It was great.

Working without a team was one of the bigger adjustments I had to make. There is no hiding from it when you are a small shop. No passing the buck, no hiding behind the work of others. I have found what it has forced me to do is really see projects and solutions for what they are. “Rose colored glasses” are one of the most dangerous things when it comes to holistic design. You have to be able to self critique.

Getting caught up in thinking that all of your ideas are the best means you’re bound to miss something. That compromises your authoritative voice. Being able to see projects from all sides, and self critiquing is a daily routine that I have to do in the absence of having other creatives sitting a short distance away. My collaborations have changed; now I seek out feedback from trusted peers, former coworkers, and other freelancers to verify and validate any concepts that I am not 100% sold on.

One of the central themes surrounding entrepreneurship of any kind is risk. Striking out on your own and starting a studio involves a lot of risk and sometimes a bit of fear. What role has risk played in starting your studio and how do you deal with uncertainty and the fears/worries of being an entrepreneur?

Fear is a powerful thing, when you can control it. When it consumes you, though, that fear begins to drive your decisions. Ultimately, you can end up compromising your integrity as fear, not authority, becomes the driving factor behind your decision making. Essentially, if you begin to react out of fear in decisions toward your business, you will quickly compromise your core values in order to try and mitigate that fear. If you are able to control your fear by acknowledging what the causes of that fear are, you can begin to plan for them. Eventually, you become quite good at playing “life chess”, as it were, learning to play two moves ahead. That type of control enables you to turn any fear into calculated variables.

Businesses that are reactionary are prone to becoming rudderless ships, letting the fear of failure consume them to the point at which they bend their core principles for quick fixes. I have found that fear drives me to continue growing who I am creatively, as my fears are driven more by the idea of becoming stagnant. So, I push myself that much harder. Ultimately, this mindset makes me a better provider for those around me.

Risk fits into this picture as well, though I believe not in the typical manner. Creatives deal with risk all the time. We just don’t realize it. As creatives we take risks every day when we open ourselves up to criticism regarding our design solutions. Every time we seek self expression, that’s risk. In business, risk fits into my earlier description of fear and calculated variables. I am a big believer in thinking things all the way through, pros and cons, good and bad, and making decisions based on looking at issues from all sides. Risk is just another variable that is acknowledged and understood and weighed with the desired outcome. The risk becomes the gut check of how much I want something.

The risk of taking on too much work is a daily struggle, but with a bit of balance it is really less of a risk and more of a known undertaking. If I can live with spending hundreds of dollars on equipment, believing that it can improve the work that I do, then I am willing to take a spin on it, even if it could break down, not work the way I wanted to, or not yield the desired results. Risk is ever present on the road to success. If you understand that risk is always present, and it is not a black and white variable but, rather a scale of grays, you will be able to find how much risk you are comfortable with.

One challenge in running your own studio is the decision to focus on a niche area or cast a wide net of services to offer. What has been your approach to that and do you see advantages/disadvantages to one way or the other?

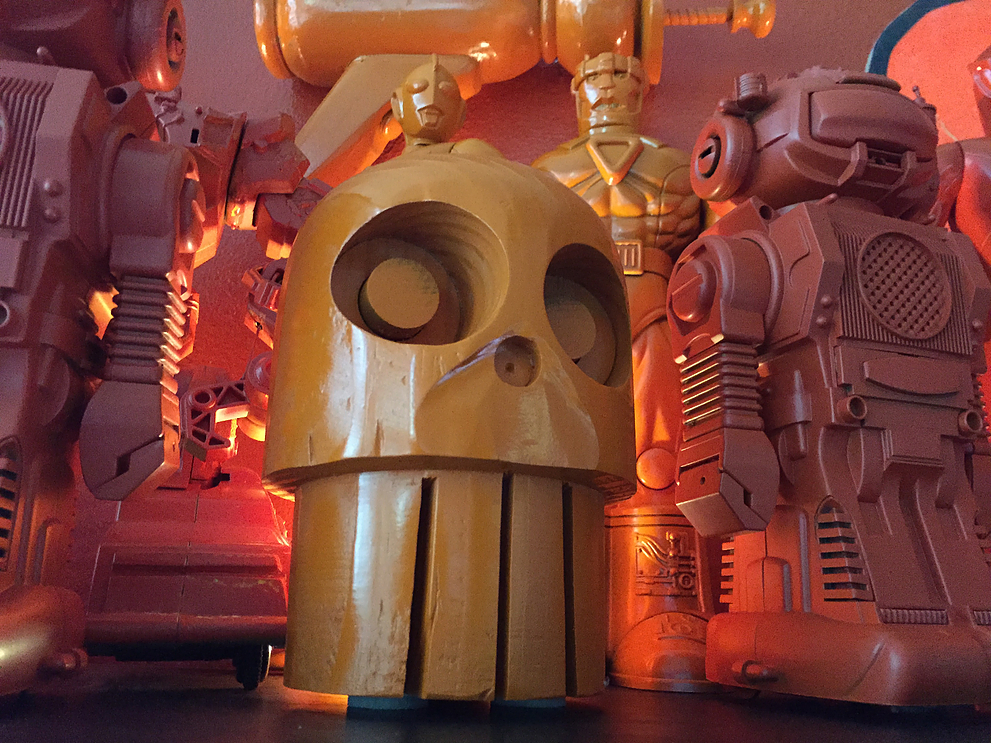

Here is a snippet from the review from my first solo gallery show that covers this question well.

Artificial Agents is worth seeing, if just for the propaganda pieces. Kappel would’ve done well to pare down the wildly differing styles, but then again, this is his first gallery exhibit. He’s like a child with too many crayon drawings and not enough refrigerator space to show them all.

I’ve never been one to take one style and stick with it. I find that broadband exploration yields more solutions than coloring within the lines and limiting yourself to one small area of design. This approach does have an adverse effect in that I do not necessarily have a signature style, which can make it difficult to get work based on illustration sometimes.

I feel, though, that professionally the more design services I can offer, the more clients seem to turn to me on jobs of varying size. Maintaining quality is the key, though. There is nothing wrong with specializing and doing one or two things extremely well. In my experience, however, the more that I can weave varying skills together, the more successful I am at being the first (and only) call that clients make.

Developing a certain business acumen is also an important skill to foster the growth of a new studio. What have been the “running your own studio” hurdles you’ve overcome as you’ve built your business?

Billing. Plain and simple. Chasing money sucks, invoicing sucks, and quantifying the value of your time is a challenge. That side of the business I would gladly hand over, but it’s not a luxury that I have at this point. I’m not a great self marketer. My work and reputation speak louder than any elevator pitch that I could ever make. At the end of the day, billing is the bane of my existence.

One of the most important resources we receive as studio owners is experience. As we do more work we become more adept at running our business. What advice would you give to a designer who is on the fence about starting their own studio?

This is where I deviate from most, as even when I had a full time gig, I was still working all hours. Maintaining that work/life balance is one of the aspects I have found the most challenging of working for myself. The off switch is a battle.

When you live in your studio, and hang out by your computer, you’re always on. Balance is something that needs to be strived for, but make no mistake: you are on all the time—you have to be. Your success or failure is your own, and the amount of time you are willing to pour into your studio will gauge that success.

Try to see things in real time. Understand that you have to move to stay ahead, but at the same time, don’t forget to take a moment to celebrate victories both big and small. Starting my own studio is the most rewarding thing I have ever done, but it’s also been work—a lot of it.

Never settle, or get comfortable, as idle hands yield no reward. I have a saying tattooed on my arm from the sculptor Constantin Brâncuși, it reads, “Create like a God, Command Like a King, Work like a Slave.” Those are the words I live by. If you can look at your work and say that you are ready to devote yourself full time, to go all in, good days and bad, then you are ready to jump out on your own.

Become your own advocate, because most times you will be the only one around. If that gives you pause, work on it. When you are ready, though, it is the best feeling in the world once you make the break and become the true master of your own fate—controller of your own creativity.

– – –

Erin Lynch is a designer, writer, and educator living in Vancouver, WA. He owns the design studio, Shop, and is an editor at The Portland Egotist. Reach out and make friends on Twitter: @erinlynch.

Erin Lynch is a designer, writer, and educator living in Vancouver, WA. He owns the design studio, Shop, and is an editor at The Portland Egotist. Reach out and make friends on Twitter: @erinlynch.