Duane King is a Portland-based consultant and creative director with a broad and varied career. He launched Herman Miller’s first websites, created packaging for Neiman Marcus and id Software, and designed innovative interactive websites at Nike. In 2011, Fast Company selected him as one of the 50 most influential designers in America (in collaboration with Ian Coyle) in part for his work on the Nike Better World campaign. This September, Duane spoke at AIGA’s Career Tools about how design helped him become a better entrepreneur, and how embarking on a personal project opened up new career opportunities.

Graphic provided by Duane King.

Finding success and satisfying design work

For Duane, successful and satisfying design work can be found by learning:

- What you’re good at

- What you like to do

- What you can charge for

The challenge is in adapting when those things change. And throughout his 20+ year career Duane has seen significant changes in the design industry.

“When I got my first job after school working for an agency, I could draw better than most people, but it didn’t matter.”

When he was transitioning from college to his first agency jobs the industry’s tools of choice were moving from analog to digital. He was skilled at drawing – one of his first professional projects was a hand-drawn logo for the board game Scattergories – but saw where the tools were heading. So, fresh out of school, Duane borrowed a frighteningly large chunk of money to pay for his first computer and developed his understanding of digital tools and techniques.

Around this time Duane fell in love with the conceptual frameworks that were the heritage of his design career. He hadn’t been taught about grid systems and pattern libraries in school, and before Google, it wasn’t easy to find examples of the Swiss Grid or the NYC Transit Authority Standards Manual.

“I worked in reverse, uncovering the heritage of the work.”

Managing design teams

He worked hard and was constantly busy. His desire for precision (and self-admitted stubbornness) led him to roles where he was in charge of the creative direction of his projects. With creative control came the opportunity to manage design teams. In school he had thought he would want nothing to do with management. But he loved inspiring his teams to do their best work by leading through hope rather than rote instruction.

Duane now had more direct contact with high-level stakeholders, and budgets to manage. He identified with the entrepreneurial side of the executive teams. Developing a business plan required creativity, research, problem-solving, and a certain amount of fearlessness in the face of risk. These were the same skills he had honed as a designer. Speaking their language allowed him to communicate the value of his teams’ designs with clarity.

“Designers are gatekeepers between corporate goals and the public. Because of that, we have a severe responsibility not to add more bad things to the world.”

Honing his design techniques, learning how to manage people, and developing business skills helped Duane build an impressive career. But the design problems he was working on started to become repetitive. And beyond that, something personal was missing from the work.

“I was just a guy at this company. I didn’t have my own identity.”

He questioned the work he was putting into the world — was it adding value, or just giving people more ways to be addicted? 20 years into his career, Duane took a sabbatical to reflect.

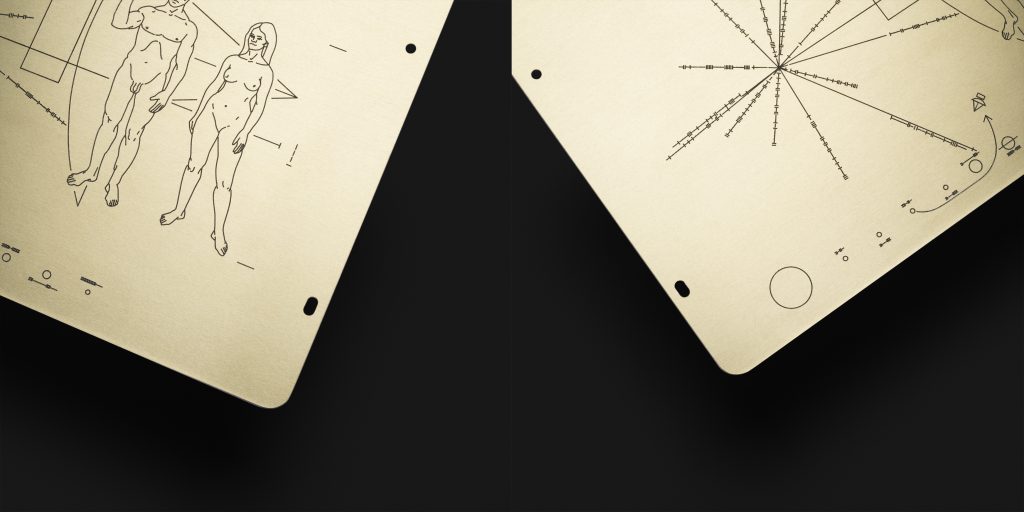

Pioneer 10

“It will be the oldest artifact of mankind. Because a billion years from now, mountain building and erosion will have destroyed everything on the Earth, but this plaque will remain intact.” — Carl Sagan

On March 3, 1972, NASA launched a probe into space on a mission to explore the solar system. It weighed 569 pounds in total, 4.2 ounces of which was a small aluminum rectangle that carried a message about humankind to other beings that it might encounter.

In 1998 Duane King, inspired by Pioneer 10, bought his first domain: pioneer10.com.

And in 2016, with his sabbatical coming to a close, Duane was thinking about the plaque again. He created vector drawings of its simple outlines of the male and female figures. He researched the type of aluminum and the process used to create the original. It seemed like a good project for a CNC router, a tool he’d been experimenting with.

Duane came across an episode of the BBC Documentary “Beauty of Diagrams” that featured the plaque. Ponciano Barbosa, the Technical Engraver for NASA in the 1970s who had worked on the original, was interviewed in the documentary. Duane did some research and found that Ponciano was alive and well. He called the shop where Ponciano was working and arranged a visit.

A template of the original plaque was hanging in the window of Ponciano’s shop. He was excited about Duane’s work and offered to help him recreate the plaque.

When Duane returned home and held the replica of the plaque which was the same size, made of the same type of aluminum, and weighed the same 4.6 ounces as the original, he was awestruck.

“Back in Portland, as I held this plaque, I realized there were only two others — one copy was 650 miles away in San Carlos, California, the other 12 billion kilometers away and moving deeper into space.”

Duane wanted to share that feeling with others. It seemed like mass-producing the plaque was technically feasible. But it would be time-consuming and expensive — a risky undertaking after not generating much income during his sabbatical.

He started by researching whether there would be an audience for this kind of product. He looked up all of the space-related Kickstarters he had backed (there were many). Most were successfully funded and he liked what he saw in the demographics of the funders.

To further gauge interest he updated his original Pioneer 10 website with a pitch for the project. He sent it to Vann Alexandra, a firm dedicated to successful crowdfunding efforts. They had also seen the success of previous space-related Kickstarters and agreed to work with him.

Things moved quickly. He laid out a business plan, detailing the costs of printing the plaque, creating the packaging (13 carefully crafted pieces), filming the Kickstarter video, and licensing the music and images. The Kickstarter would have to be fully funded for production to start, but there was no way to be sure how successful it might be. The printing estimates for the plaque were based off of assumptions that a minimum number would be produced. If the Kickstarter was more popular than expected, would he be able to scale up the printing operation without running over in costs? And what hidden costs was he not considering?

Images provided by Duane King.

He formed an LLC and gathered a team — accountant, legal advisor, web developer, videographer, motion graphics artist, copywriter, and photographer. He worked with CreateLegal, LLC and Modernist Financial, two firms with experience working on creative projects. He enlisted friends to help with recutting the Kickstarter video when he realized that shots of him talking from behind a desk were not compelling.

In the end, Duane had spent twice as much as he’d projected. And this was after not working for a year. He was nervous, to say the least.

The Kickstarter was successfully funded in 30 hours.

A month later it was 410% funded with 1927 backers pledging $286,942.

Due to the unexpected success of the Kickstarter, the production plan needed to be scaled up. Laser-engraving the plaque, as originally planned, would be too slow. Putting together the 13 meticulous pieces of packaging would take more time. And now he would need a warehouse to store all of the materials pre-shipping, another unexpected cost. Duane adapted. He found a faster production process and a better price on aluminum for larger orders, and enlisted help with putting together the packaging. Today, production is fully underway.

Images provided by Duane King.

The project was well-received by the space community. Duane was invited to visit the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory on September 15, 2017, to watch the final descent of Cassini, a spacecraft launched in 1997 to study Saturn, from Mission Control. Shortly after the viewing, he was invited to visit the NASA Ames Research Center and the SETI Institute. And the family of Carl Sagan expressed their excitement about the project.

A career-changing experience

At the end of his talk Duane made it clear that his regular design work brings in more money than he made from this project. But it was a career-changing experience. Duane had achieved his goal of celebrating and honoring the community that had inspired him since he was a kid. For them to receive it so positively was, for Duane, the most rewarding of the project. And the project added another unexpected, very specific segment to his skill set — he’s now being approached for space-related design consulting.

Thank You to Our Sponsors

52 Limited is a digital resource company connecting creative + technology talent with leading brands, marketing and engineering departments, start-ups, design firms, advertising and interactive agencies. 52 Limited began as Portland’s only locally-owned creative staffing agency and now serves some of the world’s most recognizable and forward-thinking companies in Portland, Seattle and San Francisco.

CENTRL Office is a collaborative, co-working space in Portland, OR. They provide flexible, full-service office space for some of Portland’s leading entrepreneurs, free agents, start ups, and work groups. Located on both sides of the river, in the Pearl district’s historic GE Supply Co. building, and in the Slate at the Burnside bridgehead at Couch and MLK, in the Central Eastside.

Photography of the event provided by Gabriel Partipilo. All photos are available on the AIGA Portland Flickr account.